First Example: UMP

I will first say things abstractly because it makes things simple but not necessary easy. We will need to understand the formal definition, which is the hardest thing to do:

Universal Mapping Property of M(A)

There is a function $i:A \rightarrow \vert M(A) \vert$, and given any monoid $N$ and any function $f: A \rightarrow \vert N \vert$, there is a unique $f’$, s.t., $\vert f’ \vert \circ i = f$

How to understand this? This long, abstract definition? This is actually a pretty standard math language but those 3 arrows make people confused, especially in the case that you don’t have intuition about them because this is too abstract.

From Curry-Howard-Corrsepondence, we know every proposition is actually some kind of function, by giving “a proof/an input” (phrase as ‘for arbitrary’), a proposition will “spit out a proof/an output”(phrased as ‘there exists’). We can use this similar “input/output” idea on the commutative diagram –

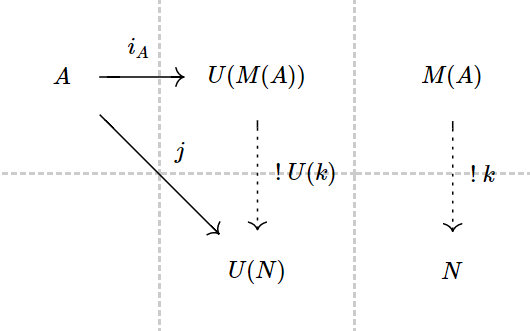

Three nodes stand for $A, \vert M(A) \vert , \vert N \vert$ respectively. Draw two normal arrows $i_A: A \rightarrow \vert M(A) \vert$ and $j: A \rightarrow \vert N \vert$, indicating the input(condition) of the proposition, then draw an arrow $U(k): \vert M(A) \vert \rightarrow \vert N \vert$ indicating the output(result) of the proposition.

You can also make an exclaimation mark on $k$ to stands for its uniqueness. This way of ‘computation‘ is easy and possible to memorize.

One thing to mention, the above diagram, on the left, stands for (part of) a category of Set. And every arrow stands for a function (see that $U(\cdot)$).

If you are not quite familar with commutative diagram, see [Barr and Well] Chapter 4. But intuitively, it is another way of saying any compositions of arrows along two paths with the same start and end are equal.

Proof: Given set $A$, the UMP for $A$ is unique (up to isomorphic).

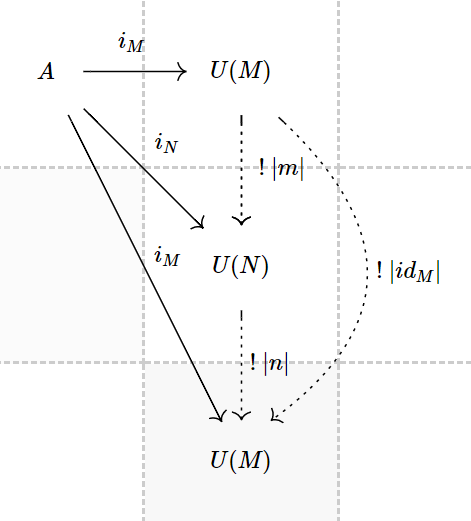

By using the diagram, the follow graph is sufficient to justify.

More formally, we have to show, if $M, N$ are both UMP for $A$ (with $i_M : A \rightarrow \vert M\vert , i_N : A \rightarrow \vert N\vert$), then $M \cong N$. By UMP, we know there will be two unique arrows $m : M \rightarrow N, n: N \rightarrow M$ s.t. $\vert m\vert \circ i_M = i_N, \vert n\vert \circ i_N = i_M$.

What’s more, if we apply the UMP property to $\vert M\vert$ and $\vert M\vert$ itself, we can conclude there is a unique arrow $k_m : M \rightarrow M$ s.t. $\vert k\vert \circ i_M = i_M$. We can judge $k_m = id_M$ by the uniqueness. Now we composite the last two equations (commutative diagram) we get from the last paragraph, $\vert n \vert \circ \vert m \vert \circ i_M = i_M$ . Since $\vert n \circ m\vert = \vert n\vert \circ \vert m\vert$ (underlying functor doesn’t alter the information), again by the uniqueness, we know $n \circ m = id_M$.

By the same trick, we can argue that $m \circ n = id_N$. $\blacksquare$

If you draw the commutative diagram, you can easily see that you are composing two ‘triangles’ together, which will yield this tedious proof quite easily. I think the diagram is really telling you how to “compute” the proof and in that way you are more closed to the reasoning and you will not get lost in the details.

Now that we know the UMP, we can go through the proof of monoid monomorphism are just injective monoid homomorphism, which is at P30 of Awodey. [Barr and Well] also has a proof which doesn’t require the usage of UMP and might be easier to understand. However, it is not phrased in the categoryical language as UMP and thus is not recommended.

UMP is a very important concept even though it is very elementary and cannot yet show the power and elegance of category theory . However it is the first time you actually prove something abstract nonsensely, and you can see it is really useful in the proof of the above prop. What’s more, if you consider free monoid using UMP as definition, it is a categorical way to think than really considering free monoid to be just a list or a concatenation of literals. This way of thinking can be more revealing. Most importantly, it is actually the first example of adjunction. If you get familar with this concept, you can master the definition of adjoint functor quite easily.