Natural Transformation are arrows of arrows

Or more explicitly, natural transformations are the arrows in the category where objects are functors.

Can you guess the definition of natural transformation?

If not, do you remember the definition of the arrow category?

Given a category ${\cal C}$, we can have a ${\cal C}^\rightarrow$

where objects are arrows in ${\cal C}$ and

arrows $f \rightarrow g$ where $f, g \in {\cal C}^\rightarrow_0$ are a pair of arrows $(h,k)$ where $h,k \in {\cal C}_1$ s.t. $g \circ h = k \circ f$

(the compose here $\circ : {\cal C}_1 \times {\cal C}_1 \rightarrow {\cal C}_1$, the subscription 0 means the collection of object, 1 means the collection of arrows)

The whole point of recalling arrow category here is to point out how ‘commutative square’ ($g \circ h = k \circ f$) can be composed into a bigger ‘commutative square’, which satisifies the prerequsite to be an arrow.

Now comes the definition of natural transformation

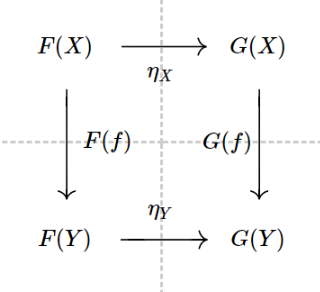

For arbitrary functors $F, G : {\cal C_1}\rightarrow{\cal C_2}$, a natural transformation $\eta : F \rightarrow G$ is a family of arrows (where indices are objects of ${\cal C_1}$) s.t. $\eta_X : F(X) \rightarrow G(X)$

and for all possible arrows $f : X \rightarrow Y \in {\cal C_1}$, the following commutative diagram holds

You will see how “commutative square” can be the reason that the functors and natural transformations can be considered as a category.

Monic components induce monic natural transformation

It is a very trivial part but I want to go through the details of this proof.

Claim: If natural transformation $\eta$, where $\eta_X$ is monoic for any object $X$, then $\eta$ is monoic as well.

Proof. Let $\alpha, \beta$ be arbitrary natural transformation.

Assume $\eta \circ \alpha = \eta \circ \beta$.

Thus $\eta_X \circ \alpha_X = (\eta \circ \alpha) (X) = (\eta \circ \beta)(X) = \eta_X \circ \beta_X$ for all $X$,

thus $\alpha_X = \beta_X$ for all $X$

which means ${}^{???}$ $\alpha = \beta$.

$\blacksquare$

Note the final sentence in the proof, we use something very similar to the axiom of function extensionality. The question is, can I do that? Can we say two natural transformations are equal as long as they are equal on each corresponding component? If only the natural transformations are considered as indexed sets.

Example: ‘Models’

Barrs and Wells define a concept ‘model’. A model for a graph is a graph homomorphism from that graph to Set. It seems very trivial.

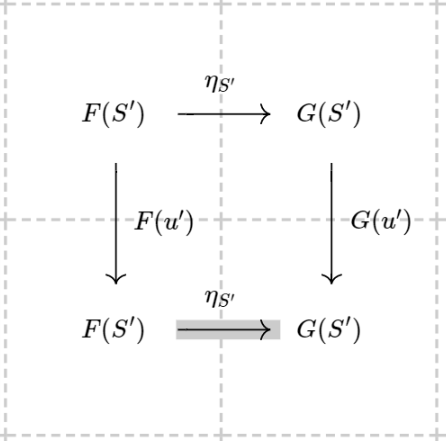

Before proceed, we define a set with structure $(S, u:S \rightarrow S)$. Intuitively, a homomophism $h: (S_1, u_1) \rightarrow (S_2, u_2)$ is just a function satisfying $h \circ u_1 = u_2 \circ h$.

Now we can draw a graph to indicate that structure. Simply a node $S’$ with a self loop labeled $u’$. The graph is named as ${\cal S}$. Now consider the category where objects are the models of ${\cal S}$. Then what are the arrows? We know a graph homomorphism is not yet a functor, but we can always force those arrows to be ‘natural transformation’ to some extent. Taking arbitrary $\eta : F \rightarrow G$ where $F,G$ are both models, the following diagram commute:

Surprisingly, $\eta_{S’}$ is exactly a homomorphism as we defined. We somehow derive the definition of the homomorphism.

The name for this concept “model” become clear: we use model to interpret this graph just as we use model to interpret a sentence in any logic theory, which yield a class of mathematical object with certain structure. Furthermore, Barrs and Wells say the category of the models are ‘essentially the same’ as the category of thost $(S,u)$ structure.

‘Model’ also gives us alternative way to interpret: we can let codomain be some category other than Set. In that way, we say “model in __ category”.

Sketches are just “formal signatures”.

Maybe “formal signature” is a bit confusing. It is just how “language” and “theory” is to “first order logic”, which can classify a class of mathematical objects, as we did in the example of ‘Models’. When the author wants to prove something in category theory or express the structure of some categories, the author would choose to draw a diagram, a graph in the book to illustrate. However, sketch is the formalilzation of these aids (these graphs). These aids, once was a part of meta-language and acceptable to be a little informal and now becomes a mathematical object.

(The following summary might be incorrect.)

We first have to formalize the diagrams.

More specifically, Barr and Wells first formalize the diagram as a graph homomorphism, where domain is called shape graph. If a diagram has codomain ${\cal G}$, we say ‘that diagram in ${\cal G}$’.

I cannot see any special reason to do so. However, to define ‘commutative diagram’ on this definition is easy. Once the codomain of the diagram (graph homomorphism) is an underlying graph of a category, we say that diagram commutes if all the path in the shape graph with same beginning and end will map to and compose into equal arrow. For example, in shape graph of diagram ${\cal t}$, non-trivial ${a_i}^n, {b_i}^m$ are edges of paths with same start and end, then $t(a_1) \circ … \circ t(a_n) = t(b_1) \circ … \circ t(b_m)$.

Addtionally, a loop on a node (as a path) has to be mapped to $id$ arrow.

What’s more, in the book, the author also draw pictures (which are graphs) to represent diagrams (yet again another meta-language, despite no ambiguity). And by convention, the shape/figure of the drawn graph indicates shape graph, and the labels indicate to what the node is mapped to. So you will see some drawn picture with two nodes as same name, which indicate the different nodes of the shape graph has been mapped to same nodes.

Now we can define linear sketch, which is just a pair of $({\cal G}, {\cal D})$ s.t. ${\cal G}$ is a graph and ${\cal D}$ is a collection of diagrams in ${\cal G}$.

A model $M$ of a linear sketch in category ${\cal C}$ is a model of ${\cal G}$ in the underlying graph of ${\cal C}$ (i.e. a homomorphism), s.t. for every $D \in {\cal D}$, $M \circ D$ commutes.

Now you can see how linear sketch strengthen the expressibility compared to just a simple graph in the example “Models”. The definition of “model” reveals the reason why linear sketch are just formal signatures. But is linear sketch really more powerful and expressful than a simple graph (in the example “model”)?

I won’t go into the details of the theories of sketches because (1). it is itself very abstract and thus time consuming to understand, (2) when a new object is introduced there are tons of new congruences needed to verify, which is again very time-consuming, (3) I feel a little too vague working on those mathematical objects:

A model of the underlying linear sketch $E$ in some category $C$ is the same as a functor on the original category: on the one hand, any functor takes any commutative diagram to a commutative diagram and so is a model …

This is a part from Barr and Wells, which I find not satisfactory because it is a little too informal for me.

I won’t go into details about sketches because my ultimate goal of category studying has becoming categorical semantic of type theory.

Example: (Co)Limit

Mix-Notation: Natural Transformation + Functors

2-Cat

are postponed indefinitely.